Corn Island

Louisville historian George Yater has called Corn Island the touchstone of Louisville's history for its role in the founding of the city (Yater 1979:2; 2001:220). It was a small island situated near the Kentucky shore of the Ohio River above the Falls. It was named Corn Island by early settlers because of the first crop raised there in 1778 (Johnson and Parrish 2007:6).

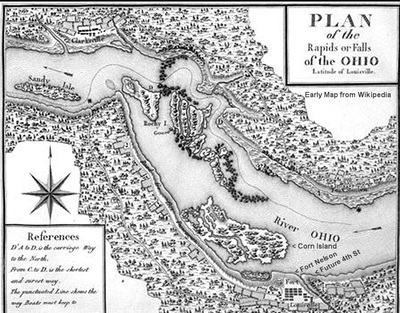

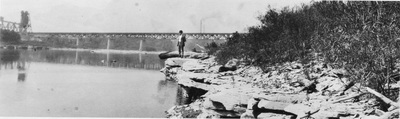

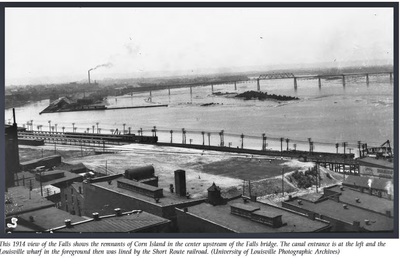

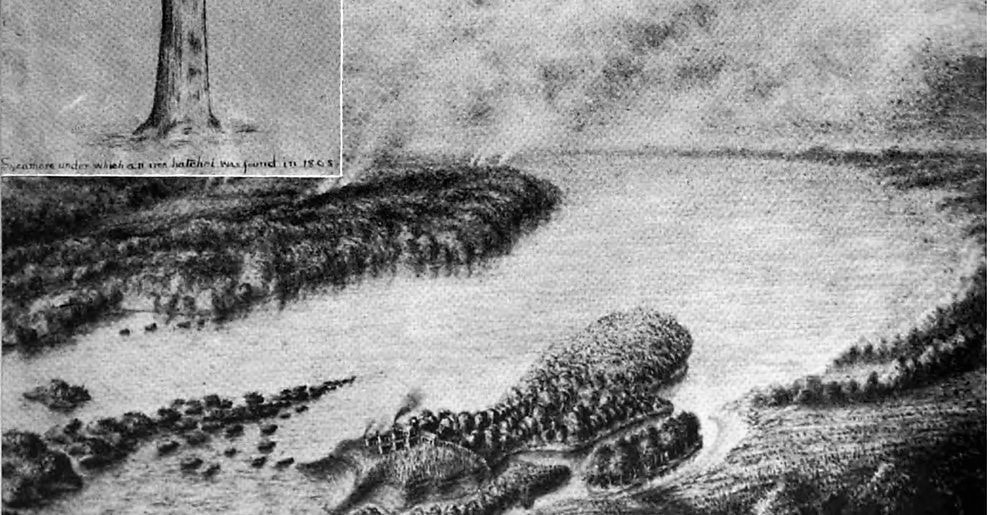

Corn Island was first surveyed by Thomas Bullitt and his party in 1773 (Wikipedia). It was mapped by Thomas Hutchins in 1766, at which time it measured 4,000 feet long and 1,000 feet wide, encompassing about seventy acres (Rave 1891). It extended along the waterfront of present-day Louisville from Fifth to Fourteenth Streets, with its southernmost point near the first river pier of the K and I Railroad Bridge. During the late 1700s, the island was covered in "great sycamores, cottonwoods, and giant cane". At very low water, Corn Island was connected to the mainland, and in one place, it was possible to wade to shore.

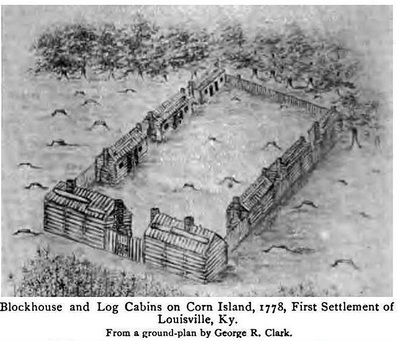

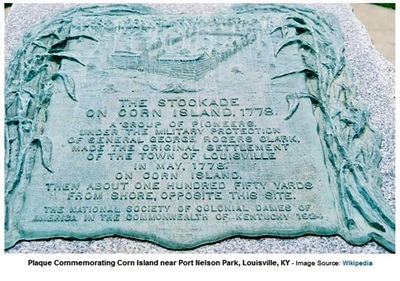

The island was first inhabited by white men when General George Rogers Clark descended the Ohio River from near Fort Pitt in Pennsylvania in 1778 with perhaps ten boats and ten to twenty families. Clark landed his flatboats on Corn Island on May 27, 1778. A blockhouse and cabins were built. Clark intended for the island settlement to be a communications post to support his military.

While Clark was gone, the pioneers scouted the mainland for future homestead sites. The core group of perhaps 10-20 families was augmented by the arrival of 300 additional souls over the course of the year. The safety of the island was eventually abandoned in 1779 as the settlers moved to the mainland of Kentucky, and a charter was obtained to found the village of Louisville.

So what four things happened to Clark's Corn Island that caused it to completely vanish?

1. Limestone: Early builders in Louisville removed limestone from the shores of Corn Island to build roads and buildings. So much limestone was removed from the island that the 43 acres recorded by its first settlers began shrinking at a rapid rate.

2. Erosion: Because so much rock was removed from the beaches of the island, many of the plants and grasses that grew on its shores were killed. These plants kept Corn Island's beaches from eroding, so as these plants disappeared the Ohio continued to wash away the island little by little.

3. Cement: During the 19th century, the Louisville Cement Company realized Corn Island's limestone was perfect for making cement. Each year tons and tons of rock was removed from the island to make cement. When the limestone became scarce above water, workers began to remove limestone from underneath the river water.

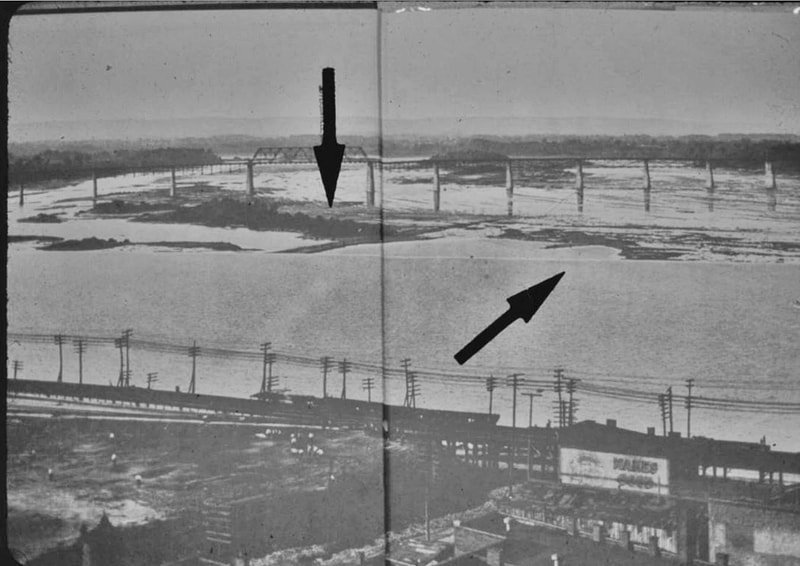

4. Falls of the Ohio Dam: Most of the island was under water by the dawn of the 20th century, but the straw that broke Corn Island's back, was the dam built on the Ohio to generate electricity for the growing city of Louisville. The Ohio River's water rose with the dam, and by 1924, the first settlement of Louisville at Corn Island was completely under water.

Also see - http://www.ciarchaeology.com/cornisland.php

Corn Island was first surveyed by Thomas Bullitt and his party in 1773 (Wikipedia). It was mapped by Thomas Hutchins in 1766, at which time it measured 4,000 feet long and 1,000 feet wide, encompassing about seventy acres (Rave 1891). It extended along the waterfront of present-day Louisville from Fifth to Fourteenth Streets, with its southernmost point near the first river pier of the K and I Railroad Bridge. During the late 1700s, the island was covered in "great sycamores, cottonwoods, and giant cane". At very low water, Corn Island was connected to the mainland, and in one place, it was possible to wade to shore.

The island was first inhabited by white men when General George Rogers Clark descended the Ohio River from near Fort Pitt in Pennsylvania in 1778 with perhaps ten boats and ten to twenty families. Clark landed his flatboats on Corn Island on May 27, 1778. A blockhouse and cabins were built. Clark intended for the island settlement to be a communications post to support his military.

While Clark was gone, the pioneers scouted the mainland for future homestead sites. The core group of perhaps 10-20 families was augmented by the arrival of 300 additional souls over the course of the year. The safety of the island was eventually abandoned in 1779 as the settlers moved to the mainland of Kentucky, and a charter was obtained to found the village of Louisville.

So what four things happened to Clark's Corn Island that caused it to completely vanish?

1. Limestone: Early builders in Louisville removed limestone from the shores of Corn Island to build roads and buildings. So much limestone was removed from the island that the 43 acres recorded by its first settlers began shrinking at a rapid rate.

2. Erosion: Because so much rock was removed from the beaches of the island, many of the plants and grasses that grew on its shores were killed. These plants kept Corn Island's beaches from eroding, so as these plants disappeared the Ohio continued to wash away the island little by little.

3. Cement: During the 19th century, the Louisville Cement Company realized Corn Island's limestone was perfect for making cement. Each year tons and tons of rock was removed from the island to make cement. When the limestone became scarce above water, workers began to remove limestone from underneath the river water.

4. Falls of the Ohio Dam: Most of the island was under water by the dawn of the 20th century, but the straw that broke Corn Island's back, was the dam built on the Ohio to generate electricity for the growing city of Louisville. The Ohio River's water rose with the dam, and by 1924, the first settlement of Louisville at Corn Island was completely under water.

Also see - http://www.ciarchaeology.com/cornisland.php

Hover over image to see caption. Click for larger image and a manual slide show with captions. Keyboard arrows can be used